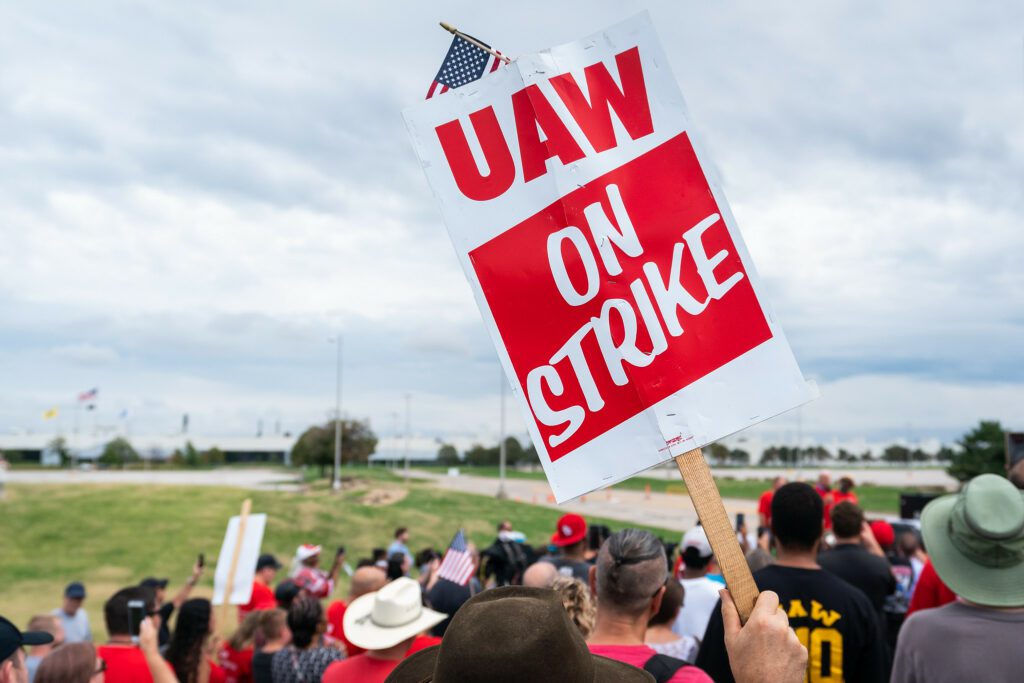

With tentative agreements in hand from each of the Big Three automakers, the United Auto Workers’ membership is now poised to vote on an historic set of contracts.

Observers have rightly celebrated the virtual elimination of wage tiers, the restoration of cost-of-living adjustments, a 25% increase in members’ top hourly pay rate, and the right to strike over plant closures as major victories for the union. But provisions addressing the companies’ domestic electric vehicle operations also represent a watershed in the fight for a just transition to a decarbonized economy.

Both General Motors and Stellantis agreed to include joint-venture electric vehicle battery plants under their master contracts with the UAW. The wage schedule for new hires at these facilities is 75% of UAW workers’ top rate elsewhere, but given how low pay is among nonunion battery workers, these represent substantial gains comparable to what existing members will enjoy.

The UAW was unable to wrest a similar concession from Ford but did ensure the new contract will cover the company’s wholly owned battery plant in Marshall, Mich. and EV assembly plant outside of Memphis, Tenn. All three automakers agreed to retain any displaced UAW member relocated to a joint-venture facility under the master contract.

The Big Three’s joint ventures were a source of much tension heading into the strike. Predictably, the companies insisted they were unable to extend contract coverage to joint-venture workers on the grounds that these workers would be technically employed by separate legal entities.

But that was always nonsense. Past joint ventures—GM and Toyota in Fremont, Calif; Chrysler and Mitsubishi in Normal, Ill.; Ford and Mazda in Flat Rock, Mich.—were all covered by the UAW’s master contracts and made great vehicles at that. The union charged that holding the battery plants at arm’s length amounted to little more than a reclassification scheme aimed at undercutting union wages and evading strict workplace safety standards.

The stakes of this dispute were high.

Domestic demand for EVs may have softened in recent months due to high prices and rising interest rates on auto loans, but growth has nevertheless been rapid. EV sales in the U.S. more than doubled in the last two years and analysts expect the market to continue expanding over the next decade.

Governments at all levels are also committing hundreds of billions of dollars in public support to subsidize the industry’s electrification. Unfortunately, most states have failed to attach robust job quality standards to their massive EV subsidy packages and federal spending through the Inflation Reduction Act does not speak to the wages of production-line workers.

This void makes unionization essential for ensuring subsidized jobs are in fact the “good-paying jobs” touted by proponents of the Biden administration’s industrial policy initiatives.

Our recent report on the IRA’s 45X income tax credit for battery production found that many of the Big Three’s announced new facilities could generate billions of dollars annually in federal income tax savings and credits, even though the companies intended to pay wages well below what UAW members currently make.

For example, Ultium Cells, General Motors’ partnership with LG Energy Solutions, is nearing completion of its 1,700-worker battery cell plant in Spring Hill, Tennessee. The facility is set to bring in $13.1 billion in 45X tax credits over the next decade, five times the $2.6 billion it cost to build it in the first place. These credits alone amount to $770,000 per job per year.

As of September, Ultium was hiring Production Operators and Quality Inspectors at Spring Hill for $20 an hour and Crew Leads for $22 an hour. Nationally, average wages for production workers in the auto sector are over $28 an hour, and under their previous contract, UAW members’ top rate reached $32 an hour.

The obstacles to labor organizing in “right to work” Southern states like Tennessee are formidable. Ultium workers’ inclusion under the GM master contract, though, will greatly strengthen the union’s pitch to prospective members at Spring Hill who stand to see their wages increase by over 30%.

As evidence of how seriously nonunion automakers are taking the UAW’s challenge, Toyota has already raised its top hourly rate and halved the time to reach it at plants in Alabama and Kentucky.

Historically, nonunion auto assembly and parts companies have sought to discourage unionization by preventing their top wage rates from falling too far below the UAW’s. While others will likely follow Toyota’s lead, the union is on the offensive and Fain has made clear his eagerness to organize workers at both nonunion “transplants”—owned by the likes of Honda, Volkswagen, Nissan, BMW, Mercedes, Kia, and Hyandai—and the reigning national champion in the EV market, Tesla.

Should the Big Three’s unionized battery plants prove crucial beachheads in the labor movement’s decades-long struggle to expand workers’ rights in the South, it will be a win for all workers. And should the UAW Stand Up Strike victories inspire communities to demand better jobs and greater accountability from companies that receive public support, it will be a win for all of us.