Note: This is the second in a new series of quarterly reports produced by Good Jobs First that look at the relationship between race, ethnicity, and economic development.

The Problem: Tax Breaks Reinforce Environmental Racism

Louisiana’s Industrial Tax Exemption Program (ITEP) has been notorious since 1936, when the oil industry engineered an outrageous power grab, taking control of tax abatements from parish (county) governments and giving it to a single state board whose members are appointed by the governor. In no other state have local governments been so disempowered.

Until recently, ITEP gave an automatic 10-year rubber stamp to tax breaks for every new, expanded, or refurbished refinery, chemical plant, or power plant in the state. Almost two-thirds of corporate personal property ended up off the tax rolls, impoverishing school districts, sheriffs’ juries, hospitals, fire departments, and libraries. By 2018, ITEP was costing public services $1.2 billion per year.

The abusive nature of ITEP was no secret, but Together Louisiana’s calculations of its costs were news. The program’s paltry benefits have been known since the late 1980s, when researchers first documented that many ITEP deals created zero new jobs. Only 4% of the projects that received ITEP tax breaks between 2000 and 2016 were for new facilities, and only 3% were plant expansions. Most were just rebuilds and maintenance spending.

The tax-revenue harms of ITEP have fallen hardest on residents of “Cancer Alley,” the 14 parishes along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans that generate a quarter of the country’s petrochemical production.

A majority of families living in Cancer Alley are Black or Brown. Many factory sites were once sugar plantations where enslaved people lived. While the state’s population is 42% BIPOC, 52% of Cancer Alley’s residents and 74% of its public-school students are BIPOC. Because this community bears the brunt of the toxins emitted by oil refineries and chemical plants, Cancer Alley is widely considered an extreme example of environmental racism.[1]

ITEP also lavished resources on petrochemical factories in the state’s southwestern corner (abutting Texas on the Gulf Coast), another region where low-income residents suffered from toxic emissions.

In short, for decades, the low-income communities of color that were systematically poisoned by the petrochemical industry also watched their tax bases depleted by handouts to those very corporations.

Map 1:

Louisiana’s Cancer Alley, by Type of Toxin[2]

Map 2: EPA Environmental Justice Map for Toxics Release to Air[3]

(Red areas are 95th – 100th risk percentile, orange 90 – 95th percentile, yellow 80th – 90th

Community Organizing Wins Abatement Reforms

The outrageous ITEP giveaways changed in 2016, when newly elected Gov. John Bel Edwards, responding to demands from Together Louisiana and other community, faith, and labor groups, signed two executive orders.[4] While he couldn’t abolish the state board, he gave local governments the right to approve or reject any deal, controlling their respective shares of affected revenue.

Edwards’ orders also tightened the state’s “gate.” They reduced the rate of 10-year abatements from 100% to 80%, and tightened up qualification rules, including a requirement that deals actually create or retain jobs (though that part was later watered down). Edwards also appointed new members to the state board, including the president of the Louisiana School Boards Association and the executive director of the watchdog Louisiana Budget Project.

To help local governments start flexing their new power, Together Louisiana picked some strategic fights. Its most dramatic victory came in 2018, when East Baton Rouge teachers voted 445 to 6 to walk out if the school board approved an ITEP deal for ExxonMobil—for a facility that had been operating for almost two years![5]

Folgers, the coalition discovered, filed six different ITEP applications for work that was already completed. Had the tax abatements been approved, Together Louisiana estimated Orleans Parish public schools would have lost $4.3 million.[6]

By 2022, it was possible to document the benefits of the ITEP reforms. The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) found that by 2021, more than $282 million was being returned each year to Louisiana public services—with an upwards trend heading to $1 billion annually, as the process of local approval made the deals more visible and harder to justify, and as the lower 80% abatement rate began moving through the ITEP pipeline.[7]

School districts, which in Louisiana rely heavily on property taxes, enjoyed the biggest gain: $113 million in 2021 and rising.

How ITEP Reforms Constitute Racial Justice

Just as ITEP disproportionately harmed Black and Brown families in Cancer Alley, the ITEP reforms have a reparative effect. Thanks to a new government accounting reform, we can quantify this measure of racial justice.[8]

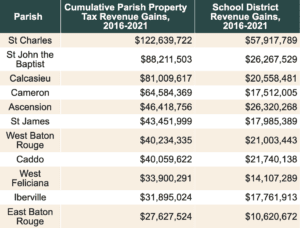

The revenue gains are geographically concentrated. Table 1 lists those 11 of the state’s 64 parishes which gained 81.5% of the total new revenue (for all public services).

Table 1:

Biggest Property Tax Revenue Gains Among Louisiana Parishes, 2016-2021[9]

Ten of those 11 school districts are in Cancer Alley or the state’s southwest corner, reflecting the geographical concentration of the petrochemical industry.

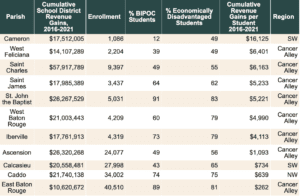

The data also reveals which students benefited the most (see Table 2). School districts in those same 11 parishes gained 83% of all the new revenue from 2016 through 2021. And with two small-district exceptions, those school districts all have student bodies that are majority economically disadvantaged and together have a greater proportion of BIPOC pupils than the state average.

The exceptions are: 1) a tiny school district in rural Cameron Parish, with only 1,086 students, which gained $16,125 per student, the largest per-pupil amount (located in Louisiana’s coastal southwest corner adjoining Texas); and 2) the very small school district of West Feliciana (2,208 students) which gained the second-most per student, $6,401 (located on the northwestern end of Cancer Alley).

Table 2:

Louisiana School Districts Gaining the Most Revenue per Student[10]

The third-, fourth-, fifth-, sixth- seventh-, eighth-, and eleventh-biggest beneficiaries per student are also school districts in Cancer Alley. They educate 91,000 students in districts ranging from 43% to 91% BIPOC.

St. John the Baptist Parish school district gained $5,221 per student; 91% of its students are BIPOC. They were overdue for some good news: A 2022 Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) investigation of toxic emissions found that children attending the Fifth Ward Elementary School in the community of Reserve had suffered decades of continuous exposure to carcinogenic air pollution, thanks to the chemical manufacturer Denka.[11] That elementary school, with 313 children, received more than $1.6 million as its share of new revenue from the ITEP reforms.

Debunking the “Business Climate” Myth

The Louisiana Association of Business and Industry (LABI) has fought the ITEP reforms at every step, claiming they discourage new investment and job creation. It has repeatedly sought to undermine Gov. Edwards’ reforms and make it easier for companies to get bigger and more automatic abatements.[12] But as Good Jobs First has always argued, tax breaks almost never determine where companies expand or relocate, and that is especially true for the oil and chemical industries in the Pelican State.

As we said publicly and to news media in 2018: property taxes make up just 0.8% of a typical refinery’s cost structure. “Petrochemical companies invest in Louisiana because it has so much feedstock in the ground, so many supplier and customer linkages, and so much pipeline and waterway and railroad infrastructure to move product. Those are the business basics that, along with labor and other inputs, make up more than 98 percent of their cost structure.”[13] A 2019 investigation of Cancer Alley by ProPublica drew similar conclusions.[14]

The IEEFA study further laid to rest the “business climate” propaganda. It found that after the ITEP reforms took effect, applications for both new projects and capital investments increased. In cases where a tax break was rejected, the project almost always proceeded anyway.

Reparative tax policy, racial justice, and a measurably better business climate: on the line as Louisiana elects its next governor.

Acknowledgment

Thanks to Erin Hansen of Together Louisiana for her assistance.

References

[1] United Nations News, March 2, 2012: “Environmental racism in Louisiana’s ‘Cancer Alley’, must end, say UN human rights experts,” at: https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/03/1086172

[2] Source: Our Daily Planet https://www.ourdailyplanet.com/story/louisianas-cancer-alley-visualized%E2%80%8B/

[3] Source: https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/

[4] https://gov.louisiana.gov/assets/ExecutiveOrders/JBE16-26.pdf, https://gov.louisiana.gov/assets/ExecutiveOrders/JBE16-73.pdf

[5] Richard Fausset, “A School Board Says No to Big Oil, and Alarms Sound in Business-Friendly Louisiana” New York Times, February 5, 2019, at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/05/us/louisiana-itep-exxon-mobil.html?searchResultPosition=2

[6] https://lailluminator.com/2023/03/13/governor-rejects-folgers-coffee-co-s-tax-exemptions-in-states-final-decision/

[7] https://ieefa.org/resources/louisiana-industrial-tax-exemption-program-itep

[8] Governmental Accounting Standards Board Statement No. 77 on Tax Abatement Disclosures. See Good Jobs First’s resources on Statement 77 at: https://goodjobsfirst.org/tax-abatement-disclosures/

[9] Source: Together Louisiana, drawn from ITEP records.

[10] Source: Together Louisiana, drawn from ITEP records.

[11] U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Educational Statistics, at: https://nces.ed.gov/ccd/schoolsearch/school_detail.asp?Search=1&SchoolID=220153002003&ID=220153002003

[12] Sam Karlin, The Advocate, February 4, 2019, “LABI, Louisiana’s largest business lobby, wants changes for ITEP tax break: Recent changes have ‘broken’ it, organization says” at: https://www.theadvocate.com/baton_rouge/news/business/labi-louisianas-largest-business-lobby-wants-changes-for-itep-tax-break/article_e0c5249c-28bc-11e9-8cec-97927a1bebc2.html.

[13] Greg LeRoy, Shreveport Times op-ed, February 2016, 2018, “Caddo Parish, Louisiana lose third of property taxes to incentives,” at: https://www.shreveporttimes.com/story/opinion/2018/02/26/caddo-parish-louisiana-lose-third-property-taxes-incentives/374435002/

[14] https://www.propublica.org/article/welcome-to-cancer-alley-where-toxic-air-is-about-to-get-worse