This is part of a series of Good Jobs First blogs that will lift up exemplary economic development practices in mid-sized cities, defined as those with a population of 50,000 to 500,000.

Our big forthcoming study of economic development practices in small- and medium-sized cities confirms that tax increment financing (TIF) remains one of the most common means of subsidizing private investment at the local level. But TIF programs vary widely in their structure, and even within the same state, localities often make very different choices about where and how to use TIF-captured revenue.

TIF programs work by diverting tax revenue, most often property tax revenue, generated within a specific geographic area (a “TIF district”) to pay for public improvements or reimburse private development costs. “Increment” refers to the increase in tax revenue resulting from redevelopment, which is typically withheld from public coffers for multiple decades.

Among our sample of cities in Michigan using of the state’s Brownfield TIF program, the city of Grand Rapids represents a compelling case study of how to ensure TIF spending is equitable, transparent, and yields the highest return on the public’s dollar.

The program was established in 1996, and like many such programs across the country, allows developers to receive property tax reimbursements for eligible costs up to 30 years after a project is completed.

Its stated intent is to stimulate investment in contaminated former industrial sites—called “brownfields”—where environmental remediation is expensive and existing infrastructure is obsolete. However, the enabling legislation gives state and local authorities wide latitude to determine whether proposed plans meet these objectives.

Grand Rapids, a city of around 200,000 residents and Michigan’s second largest, has subsidized new development through the brownfield program since its inception. In recent years, the city has distinguished itself as especially canny in its selection of projects and negotiations with applicants.

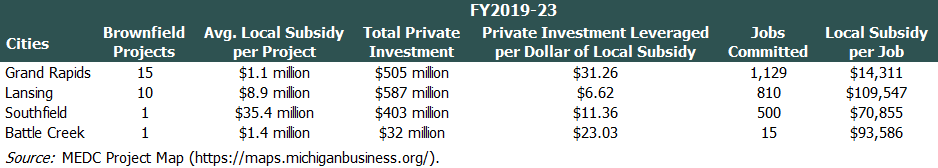

Consider our analysis below, which compares the last five fiscal years’ worth of approved projects across four Michigan cities with active Brownfield Redevelopment Authorities.

Grand Rapids stands apart for all the right reasons.

The city’s brownfield authority has approved more projects than any other city over this period while spending the least per project. Its 15 projects altogether leveraged $505 million in new private investment, the second largest total after Lansing. And yet Lansing has committed on average $8.9 million in local property tax revenue per project. That’s a return of just $6.62 for every dollar of revenue captured. Grand Rapids on the other hand leveraged $31.26, more than five times as much.

Most impressive is that subsidy recipients have committed to creating 1,129 new jobs in Grand Rapids at a cost to local governments of $14,311 per job, between one-fifth and one-ninth the cost per job paid by the other three cities.

In addition to its discerning and restrained TIF use, Grand Rapids will get high marks in our forthcoming report for conditioning public support on a broader set of community benefits and for its disclosure and reporting practices.

As part of the city’s Equitable Economic Development & Mobility Strategic Plan, brownfield applicants are required to submit an inclusion plan detailing how the developer intends to expand contracting opportunities for minority- and women-owned businesses during the project’s construction phase.

Developers can also get their annual administrative fee partially or fully waived by meeting at least one of the city’s brownfield investment criteria. These include attaining green building certification, adding on-site electric vehicle charging stations or a public transit stop, building multi-family housing, or siting their project in a Neighborhood of Focus—a set of historically disinvested and racially segregated neighborhoods south and west of downtown Grand Rapids.

No other Michigan city we examined attaches similar requirements and incentives to its brownfield TIF spending, though Lansing is to be lauded for including a local hiring commitment in its recently adopted universal development agreement.

Not content to rely on state-level disclosure, Grand Rapids’ Economic Development Department hosts its own interactive map of brownfield project locations with embedded links to the most recently amended work plan. In the Department’s annual reports, curious residents can readily find information on investment, wage, and job commitments for all subsidized projects as well as five year retrospective figures on actual project outcomes.

Altogether Grand Rapids offers an attractive model of effective TIF use to other small- and medium-sized cities grappling with a legacy of urban industrial activity and an aging building stock.

It shows that spending less and demanding more from subsidized businesses need not dampen growth. And cities that get more bang for the public’s buck find it easy to go above and beyond when it comes to program transparency because they have plenty to brag about!