This is the first blog in a two-part series investigating state and local transparency of tax increment financing programs.

Tax Increment Financing (TIF) is one of the most expensive, widely used, and controversial economic development tools in the nation. Despite this, most jurisdictions don’t report how much money they give up to TIF in their end-of-year spending reports, even while many report on other types of corporate tax breaks.

This is unfortunate but not surprising: When in 2016 jurisdictions that follow generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) began disclosing money they give up to tax abatements, some of the most expensive types of TIF were not required to be disclosed.

Despite this, some localities make their TIF disclosure very clear. Portland, Maine and Olathe, Kansas, show how well localities can disclose TIF in their annual financial reports, allowing people to see just how much money their residents are losing to private development.

TIF is a geographically targeted economic development tool that subsidizes companies by refunding or diverting some of their taxes to pay for development in a “TIF district.” It captures the increase in property taxes, and sometimes other taxes, resulting from new development, and diverts that revenue to subsidize that development. That diversion means local budgets do not get the new tax revenue they would normally get from new re/development; instead the private developers benefit from paying fewer taxes and getting free infrastructure (the intent of TIF was to direct investment to struggling communities but it’s now used for everything from luxury homes in affluent neighborhoods to adding a Nordstrom to a shopping mall).

TIFS can be structured in different ways. There is what is called an “as-of-right” TIF, when a developer with a project in a designated district gets a direct reimbursement for project costs. In a bond-based TIF, newly generated tax revenues are used to repay the bonds that were released to finance a TIF project. GASB states that “pay-as-you-go”/”as-of-right” TIFs must be disclosed in ACFRs, although it does not require TIF bonds to be disclosed, even though these deals are more common and can be very costly.

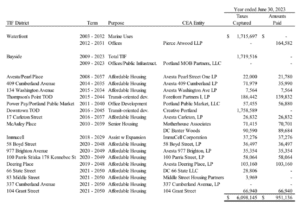

Despite this, some municipalities report TIF in their GASB 77 notes anyway. For example, Portland, Maine’s 2023 ACFR includes a breakdown by TIF district and discloses the developer name, the subsidy payment and each project purpose:

So you can see the city lost $6 million to TIF projects.

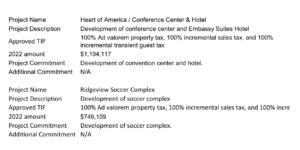

Olathe, Kansas’s ACFR has similarly good disclosure for the program that cost more than $4 million in 2022 alone. Their ACFR breaks their TIF spending by project name, and includes a project description, abated taxes, and project commitments. Here’s an example of one of those:

Many other cities do the same, but the thoroughness and completion of Maine and Olathe are models of what good disclosure look like. Both cities forgo significant revenues due to TIF, and this transparency gives citizens a chance to understand how their money is being spent. With that information, they can begin to evaluate whether the project deserves it.

Most types of TIF are economic development programs that should be covered under tax abatement disclosures. We implore GASB to revisit statement 77 to explicitly require TIF disclosure and to include all types of TIF.

Learn more about TIF on our TIF Project Page.

See more GASB 77 Disclosure on our database Tax Break Tracker.