Executive Summary

An analysis of all 24 St. Louis County and St. Louis City public school districts finds that economic development tax abatements — especially tax increment financing, or TIF — have cost students more than a quarter of a billion dollars in just the past six years.

The distribution of those lost school revenues is very uneven and disproportionately harms Black and brown students and those from low-income families.

Students in St. Louis Public Schools lose by far the most: $1,634 per student per year. By contrast, 13 suburban school districts lose less than $80 per student per year or report no losses at all.

On average, white students lose $179 per year, while Black students lose more than three times that – $610 per year.

Family income disparities are even sharper: children from low-income families lose on average five times the amount lost by students who do not qualify for free or reduced-price meals — $665 versus $133 per year.

After St. Louis, the second hardest-hit group of students are those with disabilities. The Special District of St. Louis County, which serves children with special needs residing in suburban districts, loses $1,148 per student per year.

Comparing the two largest school districts vividly explains the racial and class disparities. St. Louis Public Schools have 17,000 students, of whom 88% are Black or brown, and 100% qualify for free or reduced-price meals. The Rockwood R-VI School District has about 20,000 students, 75% of whom are white and 9% of whom qualify for free or reduced-price meals.

Yet St. Louis children lose $1,634 per year to tax abatements, while Rockwood students lose just $18 per year. That is, St. Louis students lose 91 times more than Rockwood children.

Additional specific findings:

- All told, St. Louis area schools lost at least $260.7 million to tax abatements in the six fiscal years 2017 through 2022.

- Tax increment financing, or TIF, is the costliest abatement program for both St. Louis Public Schools and all schools countywide. The next costliest is Urban Redevelopment Programs.

- The total costs of TIF and Urban Redevelopment Programs are likely much higher than officially assigned by name: Some suburban school districts reported a total of $61 million in losses by disclosing only one dollar figure for multiple abatement programs.

To remedy these problems, we recommend shielding school funding from tax abatements. We also recommend that St. Louis Public Schools be given either veto power of voting power on the St. Louis TIF Commission proportional to their share of property tax receipts. And we suggest how TIF could be used to create housing for the families of homeless SLPS students.

Key Findings: Tax Abatements and St. Louis-Area Schools

Thanks to a new public accounting rule that took effect in FY 2017 for Missouri schools, it can be reliably reported that school districts in the 24 school districts in the St. Louis area lost at least $260.7 million to tax abatements over the six years through 2022.

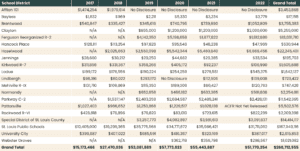

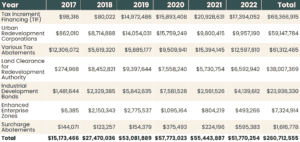

Table 1: Tax Abatement Revenue Losses 2017-2022 — St. Louis-Area School Districts

These findings for St. Louis and the 23 suburban school districts in St. Louis County come primarily from the districts’ Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports (ACFRs), the end-of-year financial statements that cities, counties, school districts, and other jurisdictions publish annually. Since FY 2017, most independent school districts in the United States have been required to report the amount of revenue they lose to economic development tax abatement programs, via a note known as Governmental Accounting Standards Board Statement No. 77 on Tax Abatement Disclosures (“GASB 77”). The same is true for most cities, counties, and other local taxing jurisdictions (For more detail, please see Appendix A).

Black and brown students are disproportionally affected by these abatements, losing more than three times as much as their white counterparts. Low-income students are also disproportionately affected, losing almost five times as much as higher-income students.

Two of the 24 school districts, Ritenour and Valley Park, did not report any tax abatement revenue losses in their financial reports. That may indicate those districts avoided any such losses. Or it may indicate the school districts are failing to comply with Statement 77. Two districts, Maplewood-Richwood Heights and Riverview Gardens, acknowledged having abatements, but deemed their costs “immaterial.”

St. Louis Public Schools Students Lose the Most

Compared to all reporting suburban school districts, St. Louis Public Schools (SLPS), an urban district, students are very disproportionately harmed by tax abatements.

This is true in both absolute dollars and on a per-student basis. Over the past six years, SLPS lost over $167 million, or an average of $1,634 per student per year. SLPS’s losses are almost double those of the suburban district with the highest per-student abatements, Brentwood. Thirteen more suburban districts report losses of less than $80, or none at all.

The Special School District of St. Louis County, which enrolls special needs students residing in St. Louis County, loses the second most per student, with an average of $1,148 per student per year.

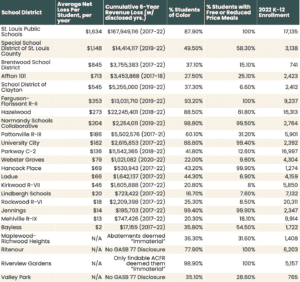

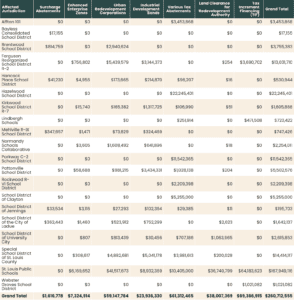

Table 2: Losses per School District, per Student, Student Body Size, and Demographics

Comparing the area’s two largest school districts vividly explains the racial and income disparities. St. Louis Public Schools have more than 17,000 students, of whom 88% are students of color, and 100% qualify for free or reduced-price meals. The Rockwood R-VI School District has about 20,000 students, 75% of whom are white and 9% of whom qualify for free or reduced-price meals.

Yet Rockwood students lose just $18 per year to tax abatements, while St. Louis children lose $1,634 per year. That is, St. Louis students lose 91 times more than Rockwood children. Rockwood lost only $2.2 million in total over all six years. SLPS lost $31 million in FY (Fiscal Year) 2022 alone.

SLPS could use the extra money. The district has the lowest teacher pay of all examined school districts – a teacher in wealthy Clayton (where fewer than 7% of students are eligible for free and reduced meals) earns $81,628, compared to $50,923 for a teacher in SLPS.

Special Needs Students Hurt Disproportionately

The second largest per-pupil loss comes from the Special School District of St. Louis County. The district loses an average of $1,148 per student, per year, with a cumulative loss of $14.4 million over six years. There is an enrollment of 3,000 students, the large majority of which are special needs students.

The district serves as the St. Louis County-wide school district for students with disabilities. It does not serve students who attend St. Louis Public Schools, as the city and county are separate entities.

St. Louis Public Schools also has a significant special needs student body population, with 2,400 disabled students. With the biggest abatement losses coming from St. Louis Public Schools and the Special School District of St. Louis, it is clear that disabled students lose more than their counterparts.

Tax Increment Financing (TIF) Costs SLPS Students the Most

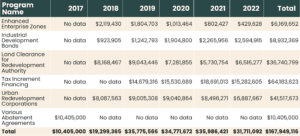

Per Table 3 below, over the past six years, SLPS students have lost $64.2 million to TIF. Other significant drains on the city’s schools include Urban Redevelopment Corporations ($41.5 million) and the Land Clearance for Redevelopment Authority ($36.7 million).

The revenue-loss trend for St. Louis schools is ominous: costs rose from $10.4 million in 2017 to $31.7 million in 2022 — an increase of more than 200%. In the years 2019 and 2021, SLPS losses approached $36 million — an even sharper revenue-loss trend.

Table 3: St. Louis Public Schools: Revenues Lost by Tax Abatement Program

While these programs were laudably enacted to encourage economic revitalization of distressed areas, the net fiscal effects cause local students to end up as collateral damage.

TIF is enabled by Section 99.800 to 99.865 of the Revised Statutes of Missouri. TIF is a geographically targeted economic development tool. It captures the increase (or “increment”) in property taxes, and sometimes sales taxes, resulting from new development, and diverts that revenue to subsidize development in the TIF district. That diversion means local public services do not get the new revenue they would normally get from new buildings and rising property values generated by the new development.

TIF has a long and very controversial history in both the St. Louis metro area and in Missouri statewide. The East-West Gateway Council, the Metropolitan Planning Organization for the St. Louis metro area, has documented its excessive use in subsidizing suburban retail developments. And on the other side of the state, the Kansas City Star 28 years ago bemoaned how programs like TIF had been created to help central cities but were now undermining them by paying companies to migrate outwards.

Perversely, then, disinvested cities like St. Louis justify the use of TIF to attract reinvestment. However, on a per capita basis, St. Louis has become an extreme outlier in the use of TIF, with about seven times the rate of Chicago, the city known for having far more TIF districts on an absolute basis than any other.

Missouri’s state auditor maintains an online database of all TIF projects and routinely conducts audits of local TIF finances. Within St. Louis County and the City of St. Louis City, there is disclosure on the corporate beneficiaries via their respective annual TIF reports.

Although some officials will cite a “but for” argument, claiming that no projects would occur without the presence of heavy subsidies, Good Jobs First rejects these claims. “But for” arguments enable developers and corporations to say, “trust me,” but the public will never know the company’s internal decision making. This information asymmetry is used as a ploy to convince the public to divert money from public goods, in order to subsidize corporations that often would have invested anyway.

Countywide Disclosure is Fuzzier

Per Table 4 below, because of its exceptionally heavy (and clearly disclosed) use in St. Louis, TIF is also the most expensive program across all St. Louis-area school districts combined, costing at least $69.3 million over the six years (of which more than $64 million is lost to St. Louis schools).

We say “at least” because 13 suburban school districts fail to disaggregate their abatement losses by program. Hence our “various tax abatements” column which totals more than $61 billion — more than any program besides TIF. We believe many if not most of those “various” lost dollars result from TIF districts.

The second most expensive program — at least as specified — is Urban Redevelopment Corporations, allowed by Chapter 353 of the Revised Statutes of Missouri. This program abates 100% of property taxes for ten years, then 50% for the next 15 years, for properties that are deemed “blighted”. Over six years, this program cost schools more than $59 million.

The third most expensive program for students is Land Clearance for Redevelopment, allowed by Section 99.700 to 99.715 of the Revised Statutes of Missouri. Over six years, this program has cost students area-wide $38 million in lost revenue.

Tax abatements bundled with Industrial Development Bonds allow localities to grant property tax discounts of up to 50% of a business’ property tax bill. Enabled in Article VI, Section 27(b) of the Missouri Constitution and Sections 100.010 to 100.200 of the Revised Statutes of Missouri, they cost schools area-wide almost $24 million.

Enhanced Enterprise Zones provide real property tax abatements to new or expanding businesses in certain specified geographic areas designated by local governments and certified by the Missouri Department of Economic Development. Allowed by Section 135.950 to 135.973 of the Revised Statutes of Missouri, they cost schools area-wide more than $7 million. The smallest program, Surcharge Abatements, was created by Missouri Constitution Article X, Section 6, and cost more than $1.6 million between 2017 and 2022.

Table 4: Tax Abatement Costs for All St. Louis-Area School Districts, by Program, 2017 – 2022

Table 5: Cumulative Net Revenue Loss by School District and Program Type, 2017-2022

Black and Low-Income Students Lose the Most

By every measure, the costs of economic development tax breaks are borne disproportionately by Black and low-income students. School districts with majority Black student bodies tend to have greater per-pupil losses, and the greatest losses are concentrated in the heavily BIPOC St. Louis Public Schools.

On average, Black students in St. Louis-area schools lose three and a third times more than their white counterparts. The average Black student loses $610 dollars per year from their education funding because of tax abatements, while white students only lose $179. Overall, students of color lose $516 dollars per year.

The average Black student loses $610 dollars per year from their education funding because of tax abatements, while white students only lose $179.

Low-income students, who due to the racialized nature of U.S. poverty are also more likely to be Black or brown, are also on the losing end of corporate tax breaks. We used the metric of free and reduced meals (FRPM) qualification as an indicator of economic need. Students who qualify for FRPM lose an average of $665 per year, while those who do not lose $133. Every year, the students who need the opportunities provided by public education the most lose five times as much of their public education dollars to tax abatements as wealthier students.

Policy Recommendations

To address the disproportionate impact of abatements on low-income students and students of color in St. Louis County and St. Louis City, we make the following recommendations:

Recommendation #1: Shield School Funding from Abatements

We recommend that every school district’s share of the property tax should simply be 100% shielded from abatements. Alternatively, school boards should be given full, sole control over their own tax bases with strict caps on what share of their revenue and how many years they can abate. No state or local agency, board, municipal or county government, or any other political sub-division besides a school board should be allowed to abate school tax revenues unless the districts are guaranteed to be “made whole” by offsets or reimbursements to the district to make up for lost revenue.

Recommendation #2: TIF Commission Reform

We recommend that St. Louis Public Schools be given veto power or voting power on the St. Louis TIF Commission proportional to their share of TIF revenue. Given that TIF is the costliest tax abatement program, it is only equitable to allow districts a say in when and how TIFs are created. Allowing school districts a say in how their money is used is key to protecting the districts’ financial stability and ensuring high educational outcomes.

Recommendation #3: Consider TIF to Aid Homeless Students

Building on precedents like Genessee County, Michigan, St. Louis should consider creating a TIF district composed of tax-delinquent, publicly owned homes near public schools. By borrowing to fund the rehabilitation of the homes for families of homeless students, such an effort could get properties back on the tax rolls while helping to stabilize school-adjacent neighborhoods.

Appendix A: Background: How is Tax Abatement Data Found?

The Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) is the independent, professional organization that establishes and continuously improves standards of accounting and financial reporting for U.S. state and local governments. GASB’s rules are known as Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).

Most states, including Missouri, legally require at least some localities (cities, counties, school districts, etc.) to conform to GAAP. Many other localities conform to GAAP as a condition of federal funding (including Title I funding to some schools) or to get the best possible credit ratings (and thus the lowest possible interest rate costs) when they borrow money by issuing bonds.

In August 2015, GASB amended GAAP by issuing Statement No. 77 on Tax Abatement Disclosures. It requires most state and local governments, including school districts, to add a note in their annual financial statements with information on revenues lost to economic development tax abatements. For most governments, the rule first applied to FY 2017 records. The Statement requires that each taxing jurisdiction report its own portion of any lost revenue, even when it loses revenue passively as the result of another government’s active tax abatement awards.

The passive loss passage of Statement No. 77 was written expressly to cover school districts, because in a large majority of states, including Missouri, abatements amount to an “intergovernmental free lunch.” Under state laws, the power to grant abatements is typically given to cities and/or counties, even though the biggest losers of revenue are the school districts. Many school districts receive some form of offsetting revenue to reduce the net cost of abatements, although none in this study reported receiving any Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILOT).

The term “tax abatement” usually refers to a property tax reduction. However, for purposes of accounting, as defined by the GASB, the term refers to any kind of foregone revenue for economic development — property, sales, or income tax.

Local governments in Missouri have complied with Statement 77 (unlike some other states), making it straightforward to track revenue lost to economic development tax breaks and compare among jurisdictions. In some states, for example, data on tax increment financing (TIF) spending is less uniformly disclosed in Statement 77 Notes. Laudably, the Missouri State Auditor maintains an online database of all TIF projects and routinely audits local TIF finances.

Appendix B: Scope and Methodology

This report covers St. Louis Public Schools and the 23 school districts in suburban St. Louis County:

- Affton 101

- Bayless Consolidated School District

- Brentwood School District

- Ferguson Reorganized School District R-2

- Hancock Place School District

- Hazelwood School District

- Kirkwood School District R-7

- Lindbergh Schools

- Maplewood-Richmond Heights School District

- Mehlville R-IX School District

- Normandy Schools Collaborative

- Parkway C-2 School District ·

- Pattonville School District

- Ritenour School District

- Riverview Gardens School District

- Rockwood R-VI School District

- School District of Clayton

- School District of Jennings

- School District of the City of Ladue

- School District of University City

- Special School District of St. Louis County

- Valley Park School District

- Webster Groves School District

Good Jobs First reviewed the Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports (ACFRs, the backwards-looking spending reports) for the 24 school districts for fiscal years 2017 through 2022.

We accessed data about the school districts’ student population size, racial composition and FRPM shares from the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education’s district report cards. These numbers were updated in November 2022.

In some cases, we corresponded and/or spoke with officials at the school districts to clarify our reading of their ACFRs.

To calculate the average abatements for students of color and low-income students, we calculated the average per-pupil abatement in each district. We then multiplied that number by the number of students of each demographic in the district and summed this across all districts. We then divided by the total number of students of the demographic across every school district. In these calculations, we omitted the statistics from the four districts with uneven disclosure (Maplewood-Richwood Heights, Ritenour, Riverview Gardens, Valley Park), whether that be because they have no disclosure or because they deem their abatements immaterial.

Appendix C: The Importance of Educational Funding

School funding has a proven effect on students’ educational outcomes. Many new papers have found direct correlations between funding increases and increases in test scores, decreases in the dropout rate, and increases in college enrollment. Another study found that public school finance reforms and increases in school spending have led to increases in wages and decreases in adult poverty, especially for low-income students. Literature on the subject has also found that teacher salary increases specifically have lowered dropout rates and lowered the racial achievement gaps.

These results show the importance of funding on educational outcomes. If per-pupil expenditures were increased, by making sure school funding was protected from the effects of tax abatements, educational and life outcomes would increase for these students. Especially when looking at the racialized nature of the impact of these abatements, these reforms are necessary in ensuring all students have equal opportunities to receive high-quality educations.

© Copyright 2024 by Good Jobs First. All Rights Reserved.

Cover photo credit: A decayed house in St. Louis. Unsplash | Jessica Christian