Note: This is the third in a new series of quarterly reports produced by Good Jobs First that look at the relationship between race, ethnicity, and economic development.

Michigan’s tax exemption for pollution control equipment costs local governments hundreds of millions of dollars every year in foregone revenue. While meant to improve corporate environmental compliance, these massive tax savings have primarily benefited some of the state’s worst repeat polluters.[1]

Not just ineffective, the state’s pollution control exemption also worsens the toll of environmental racism.

Cities like River Rouge are typical of the racially segregated, low-income urban areas that have long borne the brunt of industrial pollution and public austerity in Michigan. These places have no say when the state decides to permanently exclude pollution control equipment from the local tax base. Nor do they have any means of demanding compensation when exemption recipients are caught polluting.

Companies shouldn’t need a financial incentive to obey the law, but when they do enjoy special tax breaks, the public should hold them to the highest standard of regulatory compliance. And if Michiganders are serious about environmental and racial justice, then large profitable corporations must pay their fair share to support increased investment in public health, education, and local services.

The Problem: Lack of Local Control and Corporate Accountability

Michigan’s pollution control tax exemption is characterized by a fundamental lack of accountability: Lack of accountability for the unelected state officials abating local revenue streams and for the corporations that receive these tax breaks.

Like many states, Michigan offers companies preferential tax treatment for equipment used to mitigate either air or water pollution.[2] Such equipment is permanently exempt from the state sales tax when it is initially purchased or replaced, and from both state and local property tax millages.

To receive a pollution control exemption, all a company must do is obtain an affidavit from Michigan’s Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy certifying its newly purchased equipment will be used to reduce or dispose of harmful industrial byproducts for which the applicant has no other commercial use. This in hand, the company can proceed directly to the State Tax Commission (STC)—a three-member Treasury body whose members are appointed by the governor—for final approval.[3]

While the STC has ultimate authority to issue many of the tax breaks Michigan has created to incentivize private investment, these exemptions are unique in that applicants are not required to seek approval from a body of elected officials as well.

Public school districts and city governments lose the most from sales and property tax exemptions.

Michigan’s sales tax is levied by the state, but this revenue is almost entirely remitted to local governments. Three-quarters goes to the School Aid Fund for distribution among districts and community colleges. The state constitution requires another 10% be transferred directly to municipalities in the form of general operating grants.[4]

Property taxes in Michigan exclusively fund local governments, especially school districts and municipalities. While the state does levy a small education millage, that revenue too is earmarked for the School Aid Fund.

This makes local officials’ lack of involvement in the exemption approval process especially outrageous. No other property tax abatement in Michigan empowers the state to preempt local taxation in this way and the impact is considerable. Between 2010 and 2021, pollution control exemptions cost localities $2.2 billion; $1.5 billion of that was in foregone property tax revenue.[5]

Worse still, once an exemption is issued, local governments have no recourse to recoup their losses when a recipient violates state environmental regulations. Companies can only be compelled to repay past tax savings if an exemption was obtained through fraud or misrepresentation; regulatory noncompliance is insufficient grounds to trigger the law’s clawback provision.

As a result, local governments in Michigan passively subsidize polluters that endanger the health of their residents.

Smokestacks and Segregation Cast Long Shadows Over River Rouge

For a damning example, look to River Rouge, a small city south of Detroit.

River Rouge was incorporated in 1922, and like many of the other new municipalities hugging the Detroit River, grew rapidly as the region’s booming steel and automobile industries drew thousands of migrant workers from across the country and abroad.[6]

Black newcomers from the South lived west of the railyards bisecting the city. White families, many of them Polish immigrants, settled on the city’s east side.

Job functions at Ford’s Rouge Assembly Plant in Dearborn and the Great Lakes Steel Works were also segregated by race, with Black workers generally relegated to the lowest paid jobs and barred from supervisory positions. And yet strong labor demand in these heavily unionized sectors and their relatively high wages continued to draw new arrivals until the 1950s.[7]

To serve southeast Michigan’s industrial and population growth, Detroit Edison—the region’s private electric and gas utility, later rebranded as DTE Energy—commissioned a new coal-fired power plant on River Rouge’s waterfront. When it began operations in 1958, the plant’s three generating units were the largest in the world.[8]

The opening of the River Rouge Power Plant marked the beginning of a steady out-migration from the city that continues to the present day.

For 30 years, federal mortgage underwriters “redlined” River Rouge’s Black west side and deemed the city’s aging housing stock and working-class makeup undesirable generally.[9] Denied mortgages in River Rouge, prospective middle-class homebuyers decamped for newly built subdivisions sprawling along the state’s expanding highway system where they found cleaner air and a relative abundance of green space.

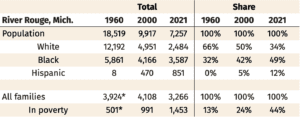

Over the next 50 years, the city’s population fell by half.

Low wages and limited savings prevented many Black residents from affording suburban homeownership in the first place, but even those who could still had to contend with rampant lending discrimination and open hostility from their white neighbors. While white residents made up two-thirds of River Rouge’s population in 1960, they were 85% of those who left over the following decades.

Rapid growth among the city’s small Mexican community did little to stem population loss overall but did contribute to the city’s demographic inversion. Since 2000, River Rouge has had a Black and Hispanic majority.

The city today is not only more racially diverse, but also markedly poorer. Economic crises battered the American steel and auto industries in the 1980s and the capital flight that followed left blue-collar workers across the region with woefully diminished employment prospects.

Today, more families in River Rouge live in poverty than in 1960 and the poverty rate has more than tripled.

*Data from 1970 Census

Note: Racial and ethnic groups are mutually exclusive. “Families” includes individuals living in households without any family relations.

Source: 1960 & 1970 Decennial Census and 5-year (2017-21) American Community Survey data retrieved from Social Explorer.

River Rouge Pays Steep Price for Pollution

Through these decades of divestment and depopulation, DTE’s River Rouge Power Plant loomed over the city, its presence leaving a lasting impact on the health of those who remained.

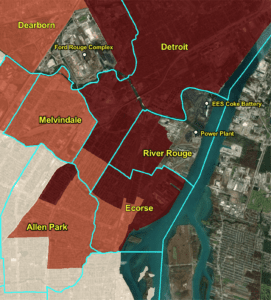

Map 1. Lifetime Cancer Risk from Air Toxics, 2014

Note: Dark red Census tracts are in the 95th -100th percentile of risk, light red tracts in the 90th – 95th percentile. Unshaded Census tracts are uninhabited or were not included in dataset.

Source: National Air Toxics Assessment data from MiEJScreen.

In 2010, the U.S. Justice Department sued DTE on behalf of the Environmental Protection Agency alleging Clean Air Act violations at four of its coal-fired power plants in southeast Michigan, including River Rouge. The Sierra Club, represented by Earthjustice, intervened in the case in 2013.[10]

The plaintiffs charged DTE with failing to modernize its pollution control systems after making significant investments at each of the plants, resulting in hundreds of thousands of tons of excess nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and mercury emissions. Exposure to these pollutants has been linked to elevated rates of asthma, respiratory and cardiovascular illnesses, cancer, and premature death.

Between 2010 and 2015, life expectancy in River Rouge was among the lowest in Michigan, six to eight years shorter than the statewide average.[11]

DTE announced its intention to decommission the River Rouge Power Plant in 2016 after spending $149 million on new air pollution control equipment at the facility to clean up its operations in the meantime.[12] The plant was shut down in the summer of 2021.

As part of its 2020 settlement with the EPA and the Sierra Club, DTE agreed to spend $5.5 million on electrifying the area’s transit and school bus fleet and $2 million on pollution mitigation projects.[13]

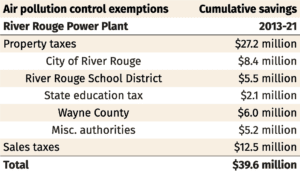

But the settlement represents a fraction of what DTE received in tax breaks. In just the last nine years of the plant’s life, the company saved over $27 million in property taxes and $12.5 million in sales taxes from exemptions on its newly installed air pollution control equipment.

Of that, $8.4 million came from the city of River Rouge and another $5.5 million from the River Rouge School District. The state School Aid Fund lost $11.5 million, and the remaining $14.3 million in losses were spread across Wayne County, various local authorities, and the state municipal revenue sharing program.

Note: Pollution control facilities depreciated according to Machinery and Equipment schedule. See Methodology Appendix.

Source: Author’s calculations from Michigan Department of Treasury property tax reports.

In other words, residents of River Rouge paid twice: First for DTE’s reckless regulatory violations in the form of worse health and shorter lives, then for its supposedly compensatory community investments.

Tax Justice is Environmental Justice

It’s unclear how much DTE had already saved on its taxes before the Justice Department filed its lawsuit. The River Rouge Power Plant had eight air pollution control exemptions outstanding in 2010 covering equipment that cost over $100 million to replace or upgrade. Many of those pollution controls were installed in the 1970s and 1980s and failed to keep emissions within permitted limits.

Not only does River Rouge have no way to seek compensation for revenue losses on DTE’s exemptions, but the city was forced by the state to forego another $8.4 million to subsidize equipment the company was legally required to install years earlier.

At a minimum, lawmakers should amend Michigan’s Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act to include a clawback condition for environmental violations. Repeat polluters should not get to keep their tax breaks.

The need for change is urgent. Less than two years after settling its lawsuit at the River Rouge Power Plant, the EPA sued DTE’s subsidiary, EES Coke Battery, also located in River Rouge, for noncompliance with the Clean Air Act. The case is ongoing, and the Sierra Club has once again intervened in support of the lawsuit.[14]

These coke ovens were originally part of the Great Lakes Steel Works and are a major source of sulfur dioxide pollution in the region. DTE acquired the battery after National Steel’s bankruptcy in 2003.

The EPA lawsuit alleges EES Coke increased its sulfur dioxide emissions after 2014 and likewise failed to install the necessary pollution controls. In the meantime, the company has saved $4.5 million from its outstanding air pollution control exemptions and will presumably seek to exempt any additional equipment it’s compelled to install.

In fiscal year 2023, River Rouge’s property tax revenue totaled just $3.6 million.[15] Between the River Rouge Power Plant and the EES Coke Battery, the city has lost just shy of $1 million a year since 2013 because of DTE’s air pollution control exemptions, fully a quarter of the city’s total property tax revenue.

While reforming the program’s clawback language would give localities a powerful new tool to discipline corporate lawbreakers, the case of River Rouge ought to make lawmakers question what’s really gained by preserving the exemption at all.

DTE Energy made nearly $10 billion in profits over the last decade and paid out $6.2 billion in dividends to shareholders.[16]

Do Michigan’s elected officials really believe such a company needs a tax break on equipment it’s legally required to install? Do they believe it is fair or just that such a company’s tax savings should come at the expense of communities most impacted by the compound harms of concentrated poverty, racial segregation, and industrial pollution?

Michiganders should reject the idea that companies must be paid to obey the law and demand their representatives prioritize sustained public investment in residents’ health and well-being. Tax justice goes hand in hand with environmental justice.

Methodology Appendix

The Michigan Treasury Department publishes annual reports listing newly issued air pollution control exemptions and the cost of the equipment acquired. Individual exemption certificates issued since 2013 are also available on the state Treasury’s website.

To estimate DTE’s property tax savings from its air pollution control exemptions, I assume all equipment is treated as personal property and depreciated according to the Machines and Equipment schedule found on the Treasury’s annual Personal Property Tax Statement (L-4175) form.

The equipment’s initial assessed value is equal to half its cost at the time of purchase, then declines according to the depreciation schedule. Because some exempted pollution control equipment would otherwise be classified as real property, and so would not depreciate as quickly, my estimate of total tax savings is likely biased downward.

Detailed millage rates used to calculate foregone revenue by local government entity are searchable on the state Treasury’s Equalization E-Filing System website.

I estimate the company’s sales tax savings as the cost of equipment acquired in a given year multiplied by 6%, the statewide rate.

References

[1] See Jacob Whiton, Good Jobs First blog, June 22, 2023, “Michigan cities fail to disclose losses from ‘pollution control’ tax break,” https://goodjobsfirst.org/michigan-pollution-control-tax-break/, and Jacob Whiton, Planet Detroit, June 21, 2023, “OPINION: How one of Detroit’s biggest polluters gets a massive tax break… for ‘not polluting,’” https://planetdetroit.org/2023/06/opinion-how-one-of-detroits-biggest-polluters-gets-a-massive-tax-break-for-not-polluting/.

[2] Kevin Potter, Darilyn Stewart, and Bruce Kessler, Deloitte, July 2017, “Credit & Incentives talk with Deloitte: Pollution control tax—state and local credits & incentives,” https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/Tax/us-tax-pollution-control-tax-credits-and-incentives-may-2017.pdf.

[3] Information on exemptions from the Michigan Department of Treasury at https://www.michigan.gov/taxes/property/exemptions/air/air-pollution-control-exemption (Air Pollution Control Exemption) and https://www.michigan.gov/taxes/property/exemptions/water/water-pollution-control-exemption (Water Pollution Control Exemption).

[4] Michigan House Fiscal Agency, “Budget Poster – FY 2022-23,” https://www.house.mi.gov/hfa/PDF/Alpha/Budget_Poster_FY23.pdf.

[5] Data collected from state tax expenditure reports available at https://sigma.michigan.gov/EI360TransparencyApp/jsp/taxexpenditurereports.

[6] See Keith Rushing and Maz Ali, Earthjustice, 2021, “Meet the Community that Stopped an Environmental Power Grab by the Trump Administration,” https://earthjustice.org/feature/dte-river-rouge-toxic-legacy, and Detroit Historical Society, Encyclopedia of Detroit, “Zug Island, https://detroithistorical.org/learn/encyclopedia-of-detroit/zug-island.

[7] For more on the region’s history of racial segregation and industrial development see Thomas J. Sugrue, 2014, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit, Princeton University Press.

[8] DTE Energy Press Release, June 4, 2021, “DTE Energy Retires ‘Small but Might’ River Rouge Power Plant,” https://ir.dteenergy.com/news/press-release-details/2021/DTE-Energy-Retires-Small-but-Mighty-River-Rouge-Power-Plant/default.aspx.

[9] Michigan State University Extension, “Redlining in Michigan: Detroit,” https://www.canr.msu.edu/redlining/detroit. For more on redlining and the role of the Federal Housing Administration, see Jonathan Rose, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Policy Brief, April 2022, “Revisiting How Two Federal Housing Agencies Propagated Redlining in the 1930s,” https://www.chicagofed.org/research/mobility/policy-brief-federal-housing-programs-redlining, and Federal Reserve History, “Redlining,” https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/redlining.

[10] Earthjustice Press Release, September 9, 2013, “Groups Join DOJ to Halt Serious Air Pollution from DTE Coal-burning Power Plants,” https://earthjustice.org/press/2013/groups-join-doj-to-halt-serious-air-pollution-from-dte-coal-burning-power-plants.

[11] National Center for Health Statistics, “Life Expectancy at Birth for U.S. States and Census Tracts, 2010-15,” https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data-visualization/life-expectancy/.

[12] Earthjustice Press Release, June 8, 2016, “Energy Progress for Detroit Communities and the State of Michigan as DTE Announces Coal Plant Retirements,” https://earthjustice.org/press/2016/energy-progress-for-southeast-detroit-and-the-state-of-michigan-as-dte-announces-coal-plant-retirements. Spending on pollution controls from property tax reports published by the state Treasury at https://www.michigan.gov/taxes/property/reports/air-pollution-control-exemption-pa-451-of-1994-part-59.

[13] Sierra Club Press Release, May 22, 2020, “Millions of Dollars of Investments Secured for Environmental Justice Communities in Sierra Club and DTE Energy Agreement,” https://www.sierraclub.org/press-releases/2020/05/millions-dollars-investments-secured-for-environmental-justice-communities.

[14] Earthjustice Press Release, September 7, 2022, “Locals Team Up with Environmental Groups to Take on Polluting EES Coke Facility,” https://earthjustice.org/press/2022/locals-team-up-with-environmental-groups-to-take-on-polluting-ees-coke-facility.

[15] City of River Rouge, “Recommended Budget, 2022 – 2023,” https://c5mf10.p3cdn1.secureserver.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/City-of-River-Rouge-Proposed-Budget-6.30.23.pdf.

[16] Annual 10-K SEC filings for DTE Energy Company available at https://ir.dteenergy.com/sec-filings/default.aspx#DTE-Energy.