Executive Summary

A small group of lesser-known nursing home chains with poor patient safety records are taking over a growing share of the long-term care industry as some of the larger players abandon the business. Federal and state regulators have been slow to keep up with ownership changes, hampering critically needed increased oversight of recidivist companies.

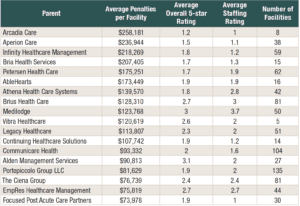

A dozen of these bad actors—some of which have doubled or tripled in size in recent years by purchasing facilities sold off by more established operators—have been averaging over $100,000 in penalties per facility, nearly three times the national level. These firms, such as Arcadia Care, Brius Health Care, Aperion Care, and Infinity Healthcare Management, also perform poorly in the federal government’s nursing home rating system, averaging only 2 on a 1-5 scale where 5 is best.

Many of the penalties paid by these chains stem from serious abuses. An Illinois-based facility operated by Aperion Care was fined $243,000 for failing to properly administer blood work resulting in a resident death. A facility tied to Infinity Healthcare was penalized over $300,000 for failing to prevent physical and sexual abuse between residents.

These findings come from an analysis of 28,000 regulatory enforcement actions covering the past five years, collected for addition to the Violation Tracker database of corporate misconduct. The penalty records were obtained from both the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and state regulators, which share responsibility for overseeing nursing homes.

Some states are not transparent about their enforcement activity. Seventeen of them fail to put information on penalty cases on their agency websites and refused to supply it in response to open records requests submitted by Good Jobs First.

We were able to fill those gaps with data provided by CMS and thus were able to determine the volume of enforcement activity for each state. This revealed wide variations across the country when measured in relation to each state’s number of facilities.

States such as Oregon, California, and Arkansas have brought an average of over 15 cases per facility over the past five years and have imposed an average of more than $100,000 in fines per facility. At the other end of the spectrum, states such as Alabama and Maine have averaged less than 2 cases and under $25,000 in fines per facility.

Such wide disparities indicate that CMS needs to do more to raise the level of enforcement in the laggard states. Given that they share oversight responsibilities with CMS, all states should be held to high, uniform levels across the country. This should include both those facilities that participate in Medicare and Medicaid and those that do not.

The new nursing home staffing requirements announced recently by CMS may improve the situation in facilities across the country, but only if they are adequately enforced.

CMS also needs to make improvements of its own when it comes to information gathering. For a long time, the agency’s data collection failed to keep up with ownership changes in the nursing home industry, especially when private equity firms began making acquisitions in the early 2000s. This made it difficult to see how these changes were affecting the quality of care.

A provision in the Affordable Care Act of 2010 was designed to rectify this by expanding ownership data collection by CMS and requiring that the data be shared with the public. That requirement was largely ignored until last year. CMS is now making a more serious effort to monitor ownership relationships, but our research for this report suggests that there are still serious gaps in the agency’s system.

Better transparency by itself will not eliminate deficiencies in the quality of care, but it will make it easier to identify the worst operators and help pressure them to improve their practices.

Introduction

There are about 15,600 nursing facilities with 1.7 million licensed beds in the United States [1]. Two-thirds of them are affiliated with 600 chains while the others are independent. Seventy percent of the facilities, with 74 percent of the beds, are owned by for-profit companies.

While several large chains such Genesis Healthcare and The Ensign Group remain active participants in the industry, some other big players have abandoned the field. [2] Kindred Healthcare announced its departure in 2017. ProMedica sold off its entire network last year despite buying out HCR Manorcare just four years prior. SavaSeniorCare, which was the 11th largest chain, went out of business earlier this year. Brickyard Healthcare, previously known as Golden LivingCenters, downsized substantially.

The disruption of larger chains has allowed other lesser-known firms to expand their operations. Many of these smaller operators increased their facility ownership by over 100 percent since 2018. At least two—Marquis Health Services and Athena Healthcare Systems—have tripled their roster of facilities during this time. As we document below, not only are these chains getting larger, they have some of the worst records when it comes to quality of care and safety.

Quality of care can be harmed during changes in ownership when it dramatically alters the operations of the facility, particularly if that home was already failing. Reductions in staffing capacity or nursing training to reduce expenses can have real impacts on the health and safety of residents, whose primary care consists of assistance with daily tasks, such as bathing, dressing, mobility, and eating.[3]

Unfortunately, nursing homes with lower care ratings are bought and sold more frequently, perpetuating a cycle of decline [4]. This short-term profit model leaves residents at risk while operators line their pockets. This study seeks to identify those chains with the worst compliance records that are also gaining control over a growing portion of the nursing home industry. It also compares the relative performance of states when it comes to enforcing federal and state requirements.

Findings

We examined facility-specific penalty data both from CMS and state-level regulatory agencies, which share oversight of nursing homes with CMS. This data, collected for inclusion in Violation Tracker, a wide-ranging database on corporate misconduct produced by Good Jobs First, focuses on the most serious penalties—those for which operators were fined $5,000 or more. This dataset, which extends back to the beginning of 2018, now contains 28,000 enforcement actions. The parent-subsidiary matching system used in Violation Tracker allows us to compare the overall record of companies that own multiple facilities. Given the opaque nature of nursing home structures, this is especially important in determining the worst violators. The parents included in this report are the 50 companies with the most facilities, as reported by CMS enrollment information.[5]

Largest Average Penalties and Cases

Using the mean data from Violation Tracker allows us to determine which nursing home operators are the most penalized in relation to size. Averaging their penalties by the number of facilities gives us a picture of the level of compliance across their operations. If we rank the per-facility averages of the 50 largest chains, we find that the average of the averages is $64,000 and the median is $44,000.

Some of the largest and best-known chains come in below these levels. Brookdale Senior Living, the largest of the chains with 346 nursing homes, averages about $14,000 in penalties per facility. Second-ranked Ensign Group is $22,000, while Genesis Healthcare, which is about the same size, has an average of $32,000. In other words, the most penalized facilities are not always those linked to the largest chains.

Our focus on this report is on those chains with the highest penalty averages—those with$100,000 or more per facility. As shown in Table 1, a dozen firms fall into this category: Arcadia Care ranks first with an average of $258,181—seven times the national level. It is followed by Aperion Care ($236,944), Infinity Healthcare Management ($218,269), and Bria Health Services ($207,405). Many of the penalties paid by these chains stem from serious abuses.

A facility operated by Infinity Healthcare Management received a $320,000 fine in 2021 for failing to protect residents from physical and sexual abuse. Multiple instances of altercations between residents were described in the statement of deficiency prepared by the regulatory agency to outline the facts supporting the citation.[6] Facility surveys by the agency also revealed that this was due to an absence of an effective governing body because the facility was structured as a limited liability company (LLC) with no oversight besides a single administrator. Consulting services were provided through another LLC with whom the regional director was employed, rather than through the facility itself. Many of the nurses at this facility stated that routine monitoring falls through the cracks without proper management.

The quality of care of many nursing homes is dependent on administrative procedures and communication between staff. An Illinois- based facility owned by Arcadia Care was fined $243,000 earlier this year for failing to follow through with an order for blood work resulting in death.[9] After complaints of weakness and feelings of impending death by a resident, one of the providers allegedly ordered lab work that was never completed, resulting in the resident being admitted to the hospital for respiratory distress. The resident later died from cardiac arrest due to severe anemia.

Bruis Healthcare: A Bad Apple Structured to Avoid Scrutiny

Brius Health Care is the largest for-profit nursing home operator in California and operates as many as 81 nursing homes and assisted living facilities across the state. Brius, like some other nursing home operators, does not brand its facilities under its own name and instead manages its operations through a complex web of individual companies.

The owner, Shlomo Rechnitz, has created a network of 80 separate corporations that oversee its nursing homes within California.[7] This structure limits owners from civil and criminal liability from adverse events. Facility ratings (and ultimately profits) are similarly protected if regulatory agencies are unable to notice a pattern of insufficient care between facilities in a chain. These protective structures have not stopped facilities linked to Brius from racking up over $10 million in nursing home penalties since 2000.

Convoluted networks allow for individual owners to profit at multiple stages of the healthcare system. Rather than relying on outside vendors, the nursing home operator will pay so-called related companies for goods, services, and rent. Since related parties do not have to disclose profits, it is difficult to find any accurate financials, and overpayments to related companies may go unnoticed.

In 2018, Brius nursing homes paid related parties $13 million for supplies, $10 million for administrative services and financial counseling, $16 million for workers’ compensation insurance, and $64 million in rent to dozens of related companies. Brius homes pay roughly 40 percent more to related parties than other for- profit nursing homes in California.[8]

While legal and common practice in the industry, this practice can funnel profits upstream without proper oversight.

Many of the chains with the largest average penalties per facility are quickly expanding. Half of the chains from Table 1 have grown their facilities since 2018.[10] Three of them have more than doubled their facility count in that time. Athena Healthcare Systems has almost tripled in size.

The dozen firms with the worst average penalties also rank poorly in the federal government’s 5-Star Quality rating system for individual facilities, which is based in part on inspection records. In a 1-5 system in which the best firms score a 5, the average of the averages for those chains is 2. None of the group has an average above 3. A big part of the problem is staffing. Those dozen firms average below 2 in the staffing component of the rating system.

Table 1. Parent Companies with Largest Average Penalties Per Facility since 2018

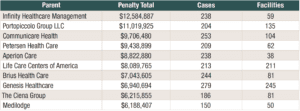

The parent companies with the highest absolute penalties and largest numbers of cases closely track those with the largest average penalties, with a few exceptions. Two of the largest operators—Genesis Healthcare and Life Care Centers of America—have a lot of cases by virtue of their sheer size, though their per- facility averages are lower. Arcadia Care and Vibra Healthcare do not make this list because their high averages are spread across few facilities.

The top 10 parents by penalty total had aggregate penalties of $77 million, nearly 10 percent of the $800 million total we examined. They account for less than two percent of the 600 different chains in the country as a whole.

Infinity Healthcare Management has the highest penalty total of almost $13 million—$7.7 million of which was incurred from just 33 cases. As shown in Table 2, the next highest penalty totals belong to The Portopiccolo Group LLC ($11 million), followed by Petersen Health Care ($9.4 million), Aperion Care ($8.8 million), and Life Care Centers of America ($8.1 million).

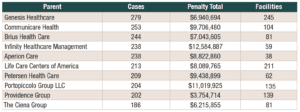

Table 3 outlines the parent companies with the highest caseloads. Providence Group and Legacy Healthcare exceed Medilodge and Athena Healthcare Systems for total cases. Despite Providence Group’s lower penalty total of $3.8 million, it has been involved in over 200 cases, resulting in a significantly lower average penalty amount than our other top violators even while operating over 15,000 beds. Genesis Healthcare has the highest number of cases since 2018 at 279, making it the top repeat offender. The next highest parent is Communicare Health (253), followed by Brius Health Care (244), Infinity Healthcare Management (238), and Aperion Care (238).

Table 2. Parent Companies with the Largest Nursing Home Penalty Totals since 2018

Table 3. Parent Companies with the Most Nursing Home Violations since 2018

Largest Individual Cases

The average penalty among the 28,000 enforcement actions we collected is roughly $29,000. There is a single penalty over $1 million; 29 over $500,000; and almost 1,800 above $100,000. This leaves 25,000 cases below six digits; with 8,500 of those between $5,000 and $10,000.

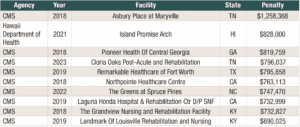

As shown in Table 2, nine of the 10 largest penalties come from noncompliance with federal regulations enforced by CMS. The only state-level enforcement action was overseen by the Hawaii Department of Health.

Asbury Place at Maryville, located in Tennessee, accounts for the largest penalty of nearly $1.3 million imposed by the CMS.

This federal action occurred in 2018 at the same time the Tennessee Department of Health issued nine fines totaling $45,000 and suspended operations of the home due to a failure to implement basic safety measures against falling. The Tennessee-based nursing home has an overall rating of 1 out of 5 on the federal rating system due to particularly deficient facility inspections and high penalty amounts.[11]

Table 4. Ten Largest Individual Penalties Imposed on Nursing Homes Since 2018

Flawed Medical Care

Nearly 90 percent of nursing home penalties collected for Violation Tracker were below $100,000, and a third of those are under $10,000—sometimes even in cases of severe harm or death.

An Iowa-based home, Oskaloosa Care Center, was fined $8,750 in May 2023 for inadequate nursing services resulting in an acute kidney injury and sepsis for a resident. The nursing staff failed to identify and intervene when a resident had elevated blood sugar and no urinary output for three days. After staff failed to replace the catheter, the resident was transferred to the hospital where he or she was found to have a urinary tract infection and an acute kidney injury due to obstructed urinary flow. According to the citation, the nurses continually passed off care for the resident rather than taking action or informing the physician. One nurse at the facility was known to ignore residents’ requests to use the bathroom, telling them they had to wait and “shaking her fist” at them if they asked. The report doesn’t indicate whether the patient survived.

This case is not unique. Many of these facilities have underpaid, overworked staff. Spontaneous falls and urinary issues are inevitable when the elderly are unstable and proper care is not provided for them. Both staff and residents are at the whim of the operator’s budget, with weak enforcement from regulatory agencies. These low penalties do little to deter greedy owners.

State Penalty Totals

To compare state compliance, we need to look at two things: the quality of disclosure and enforcement capability. We assess disclosure based upon the availability of government agency public data online or upon responsiveness to open records requests. Those requests were submitted only for penalties above $5,000 for inclusion in Violation Tracker, so we were unable to capture smaller penalties in our analysis of enforcement performance using this dataset. Instead, enforcement capability was evaluated using aggregate data covering penalties below as well as above $5,000 to better compare between states.

States vary widely in quality of disclosure. Out of 51 jurisdictions, 16 failed to provide data either through their websites or in response to our open records requests. The information provided by state agencies ranged from under 10 cases to over 5,000. For penalties above $5,000, three states had more than 1,000 cases—California (5,047), Illinois (2,464), and Arkansas (1,743). Seven states reported fewer than 10 cases, with Utah and Arizona only providing a single enforcement action above $5,000.

Using state and federal data to track enforcement ability, we analyzed the relative performance of states both by total cases and penalties, as well as cases per facility to account for variances in state size and populations. We received information from 34 states plus DC which made their enforcement data available, supplemented by federal CMS data on the rest of the country.

Since we include penalties of all amounts, this dataset is significantly larger than what was analyzed in previous sections. For all states since the year 2018, there have been 102,059 total cases, with penalties totaling over $1.2 billion. Despite the large number of cases, the penalty total reflects the fact that many of these fines are below a few hundred dollars.

As shown in Table 5, only two states have handled fewer than 100 nursing home cases since 2018 while 25 have dealt with over 1,000 cases. California ranks the highest in total penalties and caseload by a landslide, followed by Illinois and Texas with only a third as many cases.

Table 5 also includes information on cases per nursing facility. There is an average of 6.6 cases per facility across all states, with Oregon leading at 63. California (16.7) ranks the next highest with Nevada (15.7) and Arkansas (15.5) close behind. Maine ranks last with only 1.7 cases per facility. Alabama, North Dakota, and West Virginia similarly average two cases per facility or fewer.

Variations in state enforcement reflect several factors that are hard to disaggregate. While the inclusion of cases per facility helps to offset disparities in population within our data, it does not address secondary factors. More populous states have more resources for monitoring and enforcement and are likely to resolve more cases, without necessarily indicating that the homes have significantly worse performance.

Additionally, the high concentration of certain companies in different states contributes to higher numbers. The failure of states to adequately enforce wrongdoings allows many of these chains to continue operating, and even expand their facility ownership.

Table 5. State Violation and Penalty Data Since 2018, Ranked by *Total Penalties

Rank

State

Total Penalties

Cases

Number of Nursing Facilities

Cases per Facility

1

California

$145,858,894

19,524

1,170

16.7

2

Illinois

$114,076,398

6,231

694

9.0

3

Texas

$96,871,204

6,205

1195

5.2

4

Michigan

$66,792,156

2,255

430

5.2

5

Arkansas

$61,818,519

3,378

218

15.5

6

Ohio

$55,235,175

3,580

946

3.8

7

Florida

$50,071,146

5,410

697

7.8

8

North Carolina

$47,106,940

2,288

420

5.4

9

Pennsylvania

$43,663,131

2,911

672

4.3

10

Massachusetts

$37,219,863

3,383

353

9.6

11

Indiana

$34,343,825

2,630

521

5.0

12

Minnesota

$32,190,251

4,599

353

13.0

13

Missouri

$32,168,477

2,724

510

5.3

14

Iowa

$30,834,302

3,030

412

7.4

15

Wisconsin

$29,211,967

1,235

332

3.7

16

Kentucky

$28,366,525

871

276

3.2

17

Washington

$25,827,383

976

198

4.9

18

New Jersey

$20,762,497

1,280

348

3.7

19

Georgia

$20,401,835

1,214

357

3.4

20

Colorado

$20,362,234

2,145

218

9.8

21

Tennessee

$19,406,936

650

312

2.1

22

New York

$17,590,959

2,006

606

3.3

23

Kansas

$16,658,021

1,401

313

4.5

24

Maryland

$16,180,694

1,012

225

4.5

25

Oregon

$14,038,593

8,100

129

62.8

26

Virginia

$13,965,696

838

289

2.9

27

Oklahoma

$13,096,914

1,585

292

5.4

28

South Carolina

$9,806,685

1,437

188

7.6

29

Connecticut

$9,553,403

762

203

3.8

30

Montana

$9,044,159

501

62

8.1

31

Mississippi

$8,462,420

421

202

2.1

32

Louisiana

$8,280,847

954

269

3.5

33

South Dakota

$7,504,095

471

98

4.8

34

Nebraska

$7,233,314

659

185

3.6

35

New Mexico

$7,199,626

395

68

5.8

36

Rhode Island

$6,478,689

345

75

4.6

37

West Virginia

$6,475,129

250

123

2.0

38

Alabama

$5,464,165

427

225

1.9

39

Idaho

$5,304,258

374

80

4.7

40

Utah

$5,010,482

871

98

8.9

41

Delaware

$3,611,017

170

44

3.9

42

Hawaii

$3,375,082

191

43

4.4

43

Arizona

$3,322,029

453

142

3.2

44

Nevada

$2,407,044

1,051

67

15.7

45

District of Columbia

$1,987,526

69

17

4.1

46

North Dakota

$1,788,472

156

77

2.0

47

Wyoming

$1,568,077

142

36

3.9

48

Vermont

$1,303,263

102

35

2.9

49

Maine

$1,213,368

151

87

1.7

50

Alaska

$1,096,112

86

20

4.3

51

New Hampshire

$1,089,741

160

73

2.2

Inadequate Enforcement and Monitoring

Further analysis in this report is severely limited by incomplete data from both CMS and state agencies. While we collected state-level enforcement actions from nearly 70 percent of states, it remains unclear how accurate these records are.

A 2022 study by the U.S Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General found that just over half of states failed to meet CMS contract-performance standards in recent years.[12] The majority of states fell behind on survey timeliness even in response to complaints alleging serious injury. Some states did not even verify whether nursing homes corrected the deficiencies found during surveys, eliminating any opportunity to impose penalties if they did not. Since states do the heavy lifting for enforcement through these surveys, incomplete inspections affect both federal and state-imposed citations.

CMS itself has raised concerns that there are limited ways to address state insufficiencies in conducting surveys. CMS may attempt to remedy these deficiencies through corrective action plans and training to improve state performance, but these efforts are not always effective.

Though CMS provides us with two databases to track nursing home enforcement—the Penalties database and Quality, Certification & Oversight Reports (QCOR)—there are large flaws in the system. The Penalties database only reports fines imposed within the previous three years. Since many of the larger fines are appealed and this process can take many years to complete, some cases remain undisclosed to the public. Though the website archives data through 2016, these downloadable Excel spreadsheets are not updated when there is a change in penalty information.

QCOR retains its records from 2010, but it uses the same source as the Penalties database, so it is unclear whether appealed decisions make it into this database. One benefit of QCOR is that it organizes data by aggregate state information, which is especially helpful in making state-by-state comparisons, but it doesn’t identify individual cases or penalties. This eliminates the possibility of finding case- specific information from CMS prior to 2016.

Neither of these databases includes violation categories to identify what type of deficiency needs correction. The only way to find this information is to comb through the individual statements of deficiencies, case by case.Violation categories are necessary to determine the causes of misconduct and would allow us to discuss patterns in corporate behavior in more depth.

There is no central database for state enforcement of nursing homes that do not participate in Medicare or Medicaid. While 96 percent of homes participate in these programs, operators that do not meet the criteria for Medicare or Medicaid need to be monitored with even more scrutiny.[13]

Enforcement data is not the only information that is lacking. CMS provides us with corporate ownership data through several datasets, which have accuracy issues of their own. Ownership structures are self-reported and not updated accurately or regularly. While matching our parent companies to individual facilities for this report, many of the listed owners were outdated, sometimes for years. ProMedica was still included in the CMS provider list despite selling off all its facilities last year. Reporting changes in ownership is especially complex because many of these facilities are owned by larger companies masking themselves as small LLCs.

CMS is working to remedy these lapses by associating homes with larger operators. CMS recently added an Affiliated Entity Performance Measure dataset which provides information on groups of nursing homes that share common owners. A proposed rule from earlier this year would include disclosure of companies that are providing funds to homes, not only operating them.

Inadequate enforcement by regulators allows non-compliant chains of nursing home operators to keep growing with impunity. Further improvements to publicly available enforcement and ownership data are needed to hold these bad actors accountable and improve nursing home safety.

Conclusion

With the current upheaval of the nursing home industry, resident care has been put at risk. Frequent ownership changes of facilities along with shrouded corporate structures have made it difficult to hold these operators accountable. While there have been good faith efforts by CMS to improve these practices, more could be done to protect those living under the roof of neglectful companies.

As the leading agency on nursing home oversight, CMS needs more authority to better address lax states. Underperforming state agencies and those that fail to disclose their enforcement data need to be better managed and disciplined appropriately for noncompliance. Proper federal oversight would contribute to enhanced consistency among states in their enforcement activity, keeping more residents safe from harm regardless of location.

CMS needs to address the limitations of their databases so more instructive research can be done on the topic. The currently available data is a meaningful resource for residents or families who may be looking for a facility with the best care, but it does not provide academics or researchers with enough information to analyze large-scale trends.

The data provided by CMS could be augmented through the following:

- Extend available data beyond 3 years to account for cases that may take longer to resolve.

- Add categories of offenses to case-specific data to better evaluate trends of misconduct.

- Merge separate datasets into a more robust archive so data can be easier accessed and analyzed.

Though currently out of CMS jurisdiction, the small proportion of nursing homes that do not participate in Medicare or Medicaid also need to be included in the federal CMS (or HHS) databases, given the failure of states to do so.

It is difficult to define how to move forward without more concrete data surrounding the nature of nursing home violations. One theme seems to be related to staffing capacity, as many of the statements of deficiencies point to improper care by nurses.

In September of this year, CMS proposed minimum staffing requirements to enhance access to safe and high-quality care. [14] The new proposal requires that any nursing home participating in Medicare or Medicaid would be required to meet specific federal nurse staffing levels, exceeding current standards in nearly all states. These proposed requirements would cause approximately three-quarters of nursing facilities to strengthen their staffing. Nursing homes would likewise be required to have a registered nurse on site 24 hours a day. Higher levels of supervision should contribute to a higher quality of care and reduction in disciplinary actions.

This proposal also addresses workers’ compensation as many nurses are underpaid compared to other entry-level positions. States would be required to collect and report compensation for workers as a percentage of Medicaid payments. This would give CMS a better understanding of the finances of these operators, which is especially important given they are taxpayer-funded.

While laudable, better staffing levels won’t remedy underlying structural problems with the industry. Medium to large operators are able to hide their ties to individual facilities through the use of small, independent companies that technically assume ownership.

Affiliated companies—along with their owners and financial records—need to be included in all CMS databases. In the event of significant financial changes or mergers, federal and state agencies need to be promptly notified.

These recommendations only begin to explore what is needed to improve the safety and well- being of nursing home residents. The healthcare industry in general needs an overhaul of those systems which prioritize profits over people.

Methodology

This report uses a combination of data from CMS and state agencies for inclusion in Violation Tracker. We use case details for 28,000 state and federal nursing home and assisted living facility enforcement actions which exceed $5,000 and were resolved from January 1, 2018 through July 2023. While Good Jobs First was able to collect nearly 32,000 total cases related to nursing home violations dating back to 2000, the data post- 2018 provided a much more accurate analysis of state enforcement capabilities and trends in penalty totals and cases. The remaining 4,000 cases will still be included in Violation Tracker but is not used for analysis in this report.

We included all cases with a monetary penalty of $5,000 or more as long as the offender was not an individual. One agency, the New Mexico Department of Health, only issued penalties below $5,000 so it is not included in the report despite having adequate disclosure. The state-by-state comparison is the only section which includes cases below $5,000, but this data was collected at the aggregate level and does not include individual case information.

Due to variations in disclosure between states, we included cases for nursing facilities, skilled nursing facilities, and assisted living facilities – referred to collectively as long-term care facilities. Skilled nursing facilities provide more specialized medical care than assisted living facilities, which primarily help residents with daily activities.

The information was gathered from the agencies themselves – The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and state-level departments. We were able to obtain state-level enforcement activity from 34 state agencies plus the District of Columbia. For the 12 agencies that had publicly available data on their websites, we downloaded or scraped the data and put it in a standard format for inclusion in the Violation Tracker database. For all other states where the data could not be found, we submitted open records requests. For those requests that were denied, appeals were made with varying success. We were unable to obtain data from 16 state agencies which either lacked enforcement authority, denied an open records request, or simply did not respond at all. The most common explanation for a request denial was that states are not required to create new records if they do not already exist. Many of these non-disclosing states do not track nursing home fine information and instead defer to the federal agency.

Given the limitations of the CMS and state data, we were unable to categorize each nursing home violation into more detailed categories. Since Violation Tracker only captures cases with above $5,000 in penalties, cases included in this report typically exhibit more serious deficiencies which place residents in actual harm, whether that is from widespread administrative insufficiencies, abuse, or neglect. All the entries were run through Good Jobs First’s proprietary parent-subsidiary matching system prior to being added to Violation Tracker.

This system, which uses a combination of machine-generated suggested matches and human verification, identifies which of the entities named in the individual case announcements are owned by any corporations in our universe of more than 3,000 parents. These include large publicly traded and privately owned for-profit companies as well as major non-profits.

Because this report covers a single industry, we took the top 50 parents from the nursing home enrollment information provided by CMS and added that to our existing Violation Tracker parents to compile the parent universe. Where the CMS data was incomplete, we treated the chain as the parent if the facility remained on the company website or if the facility was transferred to an LLC owned by the CEO of the chain. Additional parents were manually added amidst a large controversy or news story about the facility.

The research for this report was completed in late September 2023.

Endnotes

[1] “FASTSTATS – Nursing Home Care.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 15 Dec. 2022, www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/nursing-home-care.htm.

[2] Chains were determined from CMS ownership data. Where this was incomplete, we treated the chain as the parent if the facility remained on the company website or if the facility was transferred to an LLC owned by the CEO of the chain.

[3] HHS Proposes Minimum Staffing Standards to Enhance Safety and Quality in Nursing Homes. CMS. September 1, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/hhs-proposes-minimum-staffing-standards-enhance-safety-and-quality-nursing-homes

[4] Biden-Harris Administration Continues Unprecedented Efforts to Increase Transparency of Nursing Home Ownership. CMS. February 13, 2023.https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/biden-harris-administration-continues-unprecedented-efforts-increase-transparency-nursing-home#:~:text=Nursing%20homes%20with%20lower%20Star,between%20ownership%20changes%20and%20quality .

[5] In order to find accurate facility counts, we supplemented the CMS data with outside sources, including the facilities cited on each company’s website. For Brius Health Care, we used briuswatch.org as an external source. For Portopiccolo Group LLC, we included facilities linked to Accordius Health, Simcha Hyman, and Naftali Zanziper from the CMS ownership data.

[6] Landmark of Louisville Rehabilitation and Nursing statement of deficiency and plan of correction. https://www.medicare.gov/care-compare/inspections/pdf/nursing-home/185122/health/standard?date=2021-07-03

[7] Arcadia Care Danville statement of deficiency and plan of correction. https://www.medicare.gov/care-compare/inspections/pdf/nursing-home/145753/health/standard?date=2023-03-21

[8] Nursing Homes Unmasked. The Sacramento Bee, http://media.sacbee.com/static/sinclair/Nursing2/index.html .

[9] Profit and pain: How California’s largest nursing home chain amassed millions as scrutiny mounted, The Washington Post. 2020.

[10] We were unable to find facility counts for 3 of these operators. Of the 14 we were able to gather data for, 7 have grown, 3 have remained stagnant, and 4 have downsized.

[11] Asbury Place at Maryville CMS Care Compare Details. https://www.medicare.gov/care-compare/details/nursing-home/445017?state=TN

[12] CMS Should Take Further Action to Address States with Poor Performance, http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/OEI-06-19-00460.pdf .

[13] U.S. Nursing Homes Profile in a New Report. National Center for Health Statistics. October 6, 2006. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/00facts/nurshome.htm

[14] HHS Proposes Minimum Staffing Standards to Enhance Safety and Quality in Nursing Homes. CMS. September 1, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/hhs-proposes-minimum-staffing-standards-enhance-safety-and-quality-nursing-homes