My colleagues were digging into the state of economic development subsides in Ohio – as we here at Good Jobs First do – when they came across Cincinnati resident Michelle Dillingham.

The Buckeye State interests us for lots of reasons, including how its schools are resourced. The Ohio Supreme Court ruled over 20 years ago its funding formula, overly reliant on local property taxes and lacking a way to equalize funding so schools are equitable, was unconstitutional. It’s a situation that still hasn’t been fixed.

Dillingham worked in several community nonprofits in Cincinnati and served as a legislative aide to a city councilman before joining the Cincinnati Federation of Teachers as an organizer. Over time, she began to see just how much of the city’s revenue is lost to its generous commercial and residential property tax abatements. The housing abatements last up to 15 years on any new unit or on the value of a rehabilitated home.

So Dillingham became part of a group working to reduce or eliminate their ruinous costs. Dillingham answered my questions by email from Cincinnati.

Q: How did economic development subsidies first get on your radar screen?

A: In the summer of 2017 a community-labor coalition called the Cincinnati Educational Justice Coalition (of which I’m a part) had joined our national affiliate, Alliance to Reclaim Our Schools to place a national focus on revenue campaigns for public education across the country. After years of advocating for pro-public education policies and programs, we collectively understood that it always came back to resources – more specifically, a lack of resources. Our group of parents, teachers and community members educated ourselves on school funding, and that is when we learned how much of an impact economic development subsidies had on our local schools’ funding.

Q: What’s the impact of them in Cincinnati?

A: We know our public schools suffered significant losses from this exemption of property taxes that our schools heavily rely on here. An agreement was struck in 1999 between the city and the school district to make the schools “whole” from the millions foregone by commercial tax abatements. This “making whole” only applied to commercial abatements; our schools get no payments at all for all the millions foregone by residential abatements.

In 2019, with our advocacy the percentage our schools “get back” from commercial tax exemptions was increased by 5%, and while this was an improvement, we were then stripped of the annual $5 million the original agreement provided. And we still get no restoration from residential abatements.

Q: Some people’s eyes glaze over when it comes to talking about economic development, much less something like tax increment financing (TIF). How do you relate the issue to people’s lives and self-interests?

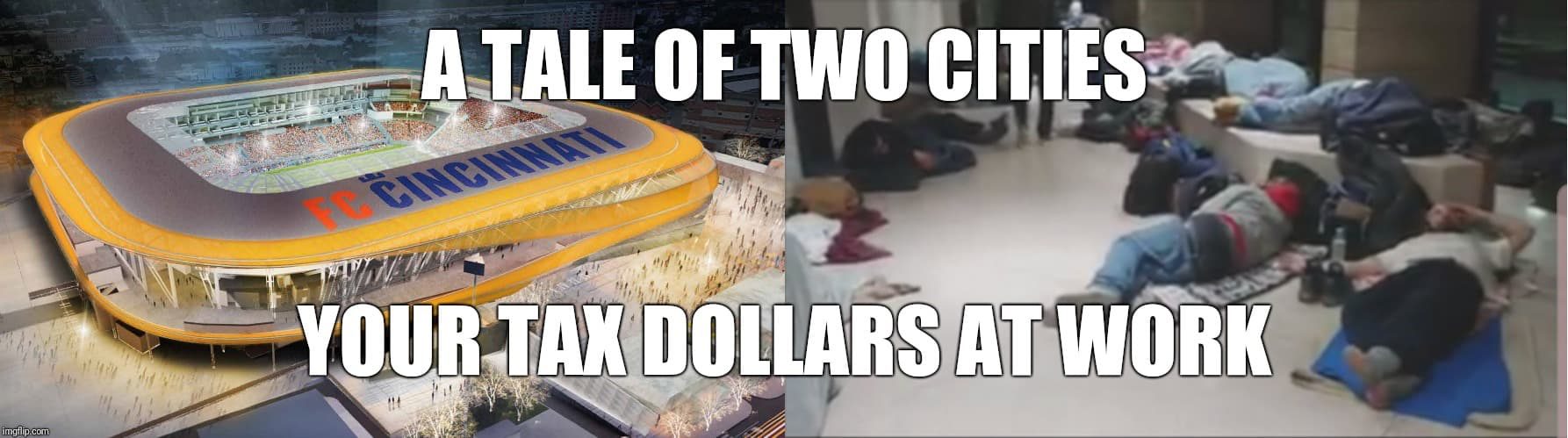

A: Economic development, tax policy… yes they can seem complicated and difficult to understand. What is NOT hard to understand is how families are seeing their property tax bills go up, how school levies are increasingly on ballots every year asking them to increase their property taxes just to maintain our schools, and how their child’s school doesn’t have enough money for after-school programs or technology. Those things are easy to understand because they are seeing it, experiencing it. In our work we connect the two things – the policy decisions to how families are impacted by those decisions. We’ve done this by holding forums, creating infographics, and even developing simple memes.

Q: Despite some community opposition, Cincinnati elected officials approved 15 new Tax Increment Financing districts in 2019. Do you believe TIF is helping boost outcomes for historically excluded neighborhoods there?

A: We have no evidence that the use of TIFs in Cincinnati has boosted any outcomes for historically excluded neighborhoods here. In fact, many of the TIF funds have been used to augment commercial development that was coming in anyway in our wealthier neighborhoods. For example, TIFs have most often been used to help with the costs of parking lots for businesses, for example. This fact helped advocates make the case that in fact TIFs were historically not being used to uplift divested communities, and that without policy change the status quo would likely continue.

Q: Like other cities, Cincinnati is experiencing a “back to the city” trend, reversing “white flight,” but segregation persists and certain areas suffer gentrification and displacement. How can incentives prevent that?

A: Economic development incentives are a powerful tool. Unfortunately, here in Cincinnati some, like our city’s residential tax abatement program, have enriched white property owners in wealthier neighborhoods while excluding African American property owners. This has the opposite effect of preventing gentrification and displacement. There are simple ways to design economic development incentive programs to be intentional about reversing gentrification and displacement. Our neighbors in Columbus, Ohio recently passed reforms of their residential tax abatement programs. So we know it is possible, which is why we continue to press the City Council to enact reforms here in Cincinnati.

5 questions with Dick Lavine: Texas’ Big Tax Breaks

5 questions with Jane Vancil: Auto-tracking subsidy outcomes

5 Questions With Ioana Marinescu : Low-Wage Earners Face Harsher Working Conditions

5 Questions with Tom Speaker: New York Breaks Up With Opportunity Zones

5 Questions with Joel Bakan: Ending Corporations’ Stranglehold on Society

5 Questions with Patricia Todd: Alabama’s Transparency Problem