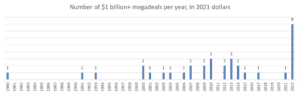

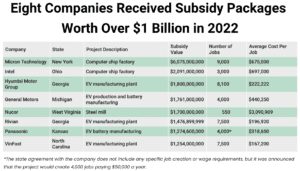

It used to be rare when a company wrested more than $1 billion from the public to open a facility. This year, that changed. In 2022, according to Good Jobs First’s analysis, there were eight economic development deals in which companies received at least $1 billion in subsidies — for a single facility. That’s an all-time record.

The 2022 list of mega-recipients is dominated by electric vehicle and EV battery factories and by microchip fabrication facilities. Five of the eight deals exceed $1.5 billion each and one — New York’s outlay for Micron at $6 billion and counting — is the third-largest subsidy package in U.S. history.

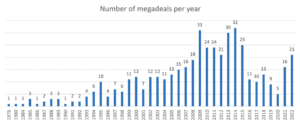

Megadeals of all sizes — any deal that provides $50 million or more of public money to an individual project — also spiked. So far in 2022 — and the year is not over! — states and communities have committed at least $19.2 billion to megadeals. In current dollars, that makes 2022 the costliest year in U.S. history; when adjusted for inflation, in 2021 dollars, only one year was costlier (and it included a $10 billion deal that was later rescinded).

The Billion-Dollar Subsidy Club

Twenty-twenty-two started with a bang. In January, a bill to provide $1.7 billion to an unnamed company sailed through the West Virginia legislature. (It was later revealed to be the top U.S. steelmaker, Nucor.) Ironically, this fast passage, in a process that lacked any transparency, happened the same day a noted expert was set to testify on the harms of corporate subsidies. The year neared its end with a splash, too, when in October New York provided microchip maker Micron over $6 billion in tax breaks and infrastructure improvements, the third largest subsidy deal in U.S. history.

Altogether, 2022 produced eight $1 billion+ deals — equal to the previous nine years combined!

When a package crosses the $1 billion mark, the financial risks become much higher for states and communities. At that point, the main justification for a subsidy – jobs – becomes so expensive that each position now is costing six or seven figures. The average per-job cost of those eight massive megadeals was about $726,000; the West Virginia Nucor deal is even higher and could exceed $3 million per job. Even at $726,000 per job, it is impossible for the public to recoup as many tax dollars from those new jobs.

Massive megadeals come with opportunity costs that can exacerbate racial inequality too. Every dollar not collected because of economic development subsidies is a dollar lost from public services such as schools, food assistance, health care, or affordable housing. Such programs make people more equal, especially Brown and Black kids who disproportionally have been locked out from accessing the country’s wealth. Instead, tax savings that companies enjoy are enriching their owners and shareholders, most of them being White men.

One reason why corporations end up with such luxury deals is secrecy and corporate dominance of the economic development process. Corporations push for non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) which prevent public officials from talking about deals or even disclosing company names before subsidy packages are announced. When in early 2022, Kansas approved a massive subsidy package of over $1.2 billion to an unnamed company, the state’s lawmakers were banned by NDAs from disclosing the recipient’s identity or the contract details. The public learned only after the deal was awarded that it was for Panasonic. This secrecy left the public with no input or oversight of the deal.

If it had seen the proposed deal, the public might have disapproved of it: the state contract does not require Panasonic to create any specific number of jobs or pay any specific wage.

This secrecy and lack of accountability looms over other deals too. Unproven electric vehicle start-up Rivian, which was provided almost $1.5 billion by Georgia, is required to pay workers only $20 an hour with no cost of living increases through 2046, hardly enough to support two working adults with one child. And in West Virginia, Nucor workers might be coming from Ohio or Kentucky, leaving only a limited number of jobs to local residents who paid dearly for them.

All megadeals spike

The increase in $1 billion+ megadeals is a part of a larger troubling trend. In 2022, we found 21 megadeals (again, deals ≥$50 million), the most in seven years and as many as 2020 and 2021 combined. With delayed disclosure of many deals, the 2022 count will likely climb for several more months into 2023.

Depending on whether you account for inflation, 2022 is the most or second-most expensive year ever for megadeals. The $19.2 billion price tag for 2022 is tops in current dollars, or second place to 2013 counting for inflation (when a single deal for Boeing worth $10 billion in 2021 dollars was awarded, then later withdrawn as part of a WTO trade dispute settlement with the European Union and Airbus).

Our $19.2 billion total is conservative and incomplete. The true figures are hidden behind poor public transparency practices, NDAs, and project code names. New York’s $6 billion to Micron, for example, includes 20-year state tax breaks and upfront infrastructure costs, but it does not yet include the value of local property tax abatements that the company will get for 49 years.

Amazon and other big-subsidy seekers have become more secretive in recent years, delaying full disclosure of public costs. Georgia held up the details on its $1.8 billion for Hyundai for months — then released them late on a Friday afternoon to minimize media coverage.

Politicians hiding costs aside, why should states be on a megadeal spending binge? You’d never know that unemployment is near a 53-year low, job openings outnumber job seekers by a ratio of 1.7 to 1, and health experts say another coronavirus spike is all but certain this winter.