Last year, the Texas state legislature mandated the Comptroller’s office to create a new database to let the public see how much money was going toward a program that directs massive amounts of public subsidies to companies.

The controversial program known as Chapter 380 and Chapter 381, for their place in the state’s tax code, is allegedly to spur economic development, but as in-depth investigation revealed last year, it has little accountability: there are no time limits on subsidy deals so some agreements can last decades, there is no specific job creation requirements, companies might pay no penalties if they don’t meet their obligations, and there is no limit on how much public money can be funneled to companies.

The Comptroller has just released the database and the good news is that finally there is some transparency around the program. Unfortunately, the database falls short when it comes to providing the public with easy and comprehensive access to data on how much public resources companies have extracted from localities and in exchange for what.

First, let’s talk about what the database does have. For the first time, the public can see which companies have agreement with which localities, and how many. Amazon, which has gotten at least $4.86 billion in public subsidies across the U.S., has for example 13 agreements with seven localities, four in Dallas alone. Richardson, a town northwest of Dallas, has had the largest number of deals over the years, 290 – many seem to be one-time payments to individuals for home improvements.

We can also see how long the agreements last: for example, the longest agreement is a 60-year deal between Dell and Round Rock (as the Houston Chronicle noted, Dell earned $4.6 billion in profits in its most recent fiscal year).

Copies of the agreements are also a valuable addition to the database.

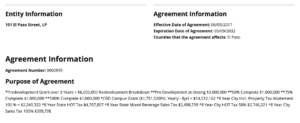

But there are huge, inexcusable information gaps. For starters, experts have pointed out that some agreements are missing from the database. And it is impossible to account for how much the program costs localities across the state. Subsidy amounts and company commitments (like how many new jobs they plan to create) are missing from too many entries. If this information is available, it is under “Purpose of Agreement” and only in a narrative format limited to 600 words. The lack of uniformity makes whatever data is available hard to compare and analyze.

Take the following example, between a company called 101 El Paso Street, LP. The Purpose of Agreement lists multiple dollar amounts and projects that are difficult to decipher:

There are also hundreds of LLCs, or Limited Liability Companies, which make finding the actual corporate owners in some cases impossible.

Some of the details of the deals and company obligations are in the attached text of the agreements. But even if one goes through the painstaking exercise of extracting relevant data from thousands of agreements, we still might not be able to answer basic questions: how much companies are getting, how many jobs are being created, what the jobs pay, what kind of investments the company is making. In other words, the basic information that allows a community to determine whether the company deserved their money is missing from the database.

An example is this one between Lancaster and Wayfair:

The database feels like a lost opportunity especially because Texas has experience with good quality disclosure. Another generous subsidy program, known as Chapter 313, which abates selective companies’ property taxes that otherwise would go to schools, has one of the best disclosures in the country. Even if it is far from being perfect, that database has subsidy amounts, jobs, investment, and many other data points. All project-related documents are posted to a project webpage and available ahead of subsidy final approval. But like the new Chapter 380/381 database, the Chapter 313 database also lacks an easy access to project-level aggregated data. In both instances what we are missing is a downloadable spreadsheet which would list companies, the amount of subsidies promised and paid out, projects location, job, wage, investment promises and outcomes (although the Comptroller makes such spreadsheet available via a freedom of information request for Chapter 313 deals; thanks to Dick Lavine of Every Texan for the hint).

The public can and should pressure the state legislature and the Comptroller’s office to improve the database. Then, residents could easily see for themselves whether it’s a program worth keeping or whether it’s time to end it and put their money instead into reducing class sizes, updating energy infrastructure, improving health care or any other number of needs that money could otherwise be spent on.